A Month in Siena 10/16/2023

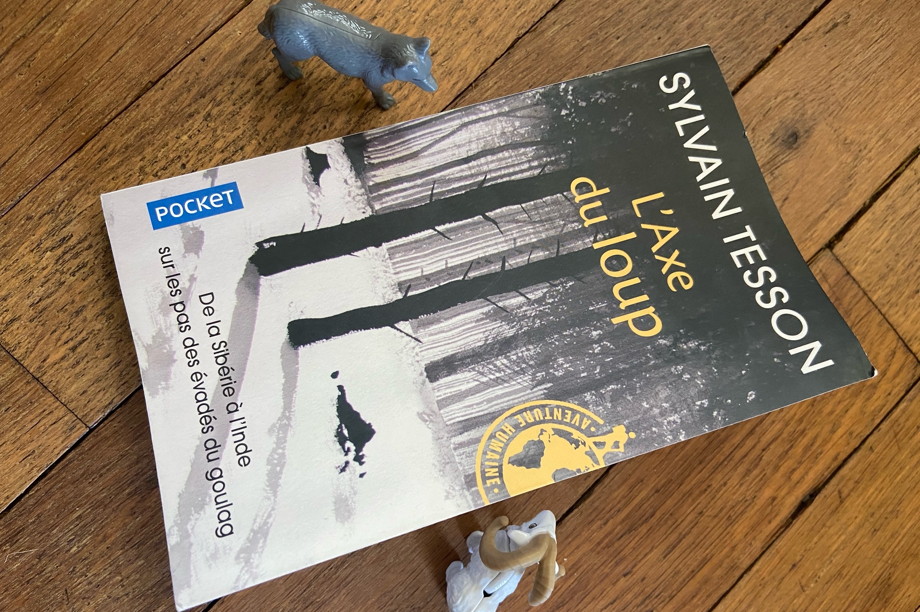

L'axe du loup

by Sylvain Tesson

Review: L'axe du loup (The Wolf Axis, 2007), by Sylvain Tesson. Arrangement by Francis Tann. February 2022.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Return to Blog Home

February 28th, 2022 at 4:12pm

Please consider disabling your ad blocker, it disrupts site functions in addition to blocking ads. Thank you!

It starts with a Polish cavalry officer.

Captured by the Soviets in 1939, Slawomir Rawicz is sent to a labor camp in Siberia.

He later escapes with six other prisoners. They travel south through Siberia, Mongolia, the Gobi Desert, Tibet, and finally into India. The group avoids or confronts the elements, bears, informants, mountain ranges, disease, lack of food, and an astonishing distance. Three people die en route.

Background on this series is here.

"Alcohol, sausage, live pigs," Tesson writes. "I'm living a Muslim's nightmare."

In 1956, Rawicz publishes The Long Walk, his story of the escape. The book is immediately discredited by explorer Peter Fleming, then Tibetan scholar Hugh Richardson in 1957, writer Patrick Symmes in 2003, and the BBC in 2006.

Among the critiques:

- Rawicz says he went twelve days without water

- The topographical descriptions of the Gobi Desert are demonstrably false

- Rawicz claims to have met yetis in the Himalayas—that's right: yetis

Enter the Frenchman

Some fifty years later, French travel writer Sylvain Tesson recreates Rawicz's journey, not to judge whether The Long Walk is authentic, but rather "to celebrate the spirit of escape." He vows to do so, as the English say, by fair means. "By horse, on foot, or on a bicycle. I find it dishonest to tackle geography armed with a motor."

By fair means or not, most people throughout the centuries have traveled laterally across Siberia, Mongolia, and Tibet. The only creatures known to move from north to south? Wolves. Animals known for their freedom and independence. (Tesson adds, is anyone more motivated by liberty than a fugitive?)

Rawicz's route, and now Tesson's, run along "the wolf axis."

I would love to see Lake Baikal, but I want a quick drop-in and an even faster exit—and that's not possible. |

The voice

The author has a gift for varying the conceptual rhythm of his prose. Exposition, anecdote, observation, contemplation—they intertwine easily, and the transitions are almost always natural. He has a tendency to reach for the grandiose, however, and those phrases can be awkward. Even then, something beautiful often emerges from his imagery.

I spend my last night before reaching the capital in a yurt, fetus of felt, a recreated world layered upon itself, with its only opening the tunduk, this orifice piercing the keystone, the center of the egg, the fontanelle by which our dreams disappear into the night.

Eight months later, we still don't know whether Rawicz is telling the truth in The Long Walk, but we've learned a lot about Tesson and the lands through which he has traveled.

Is that enough?

Russia

After taking a train from Paris (note that he traveled across Siberia), Tesson arrives in Neryungri, in eastern Russia.

My plan (in Russia you must always have a plan) is as simple as the fugitives' ambition was pure: get to Yakutsk, find the ruins of a gulag in the region Rawicz describes, and, from there, head south without stopping, until, after six months or a year, I reach the jungles of Bengal.

Someone drives him north to the city of Yakutsk, he finds an abandoned camp, and...Voilà, c'est parti.

Much discussion, understandably, is given to bears. Tesson has no weapon, and he summarizes all the advice the locals have given him in case he meets one: Don't talk to the bear. Hit a tree with a stick to scare it. Don't look it in the eye. Etc, etc. The best advice? Try not to come across any.

He continues toward Lake Baikal, hiking through the forest, meeting people in villages, drinking vodka, crossing waist-deep rivers...and counting pigs.

The video above is a different Tesson project, but it takes place on Lake Baikal.

The porcine enumeration happens spontaneously. One night, Tesson is asleep in what he believes to be an abandoned barn. A farmer transporting fifty pigs awakens him angrily, disabusing the trespasser of his notions.

Tesson explains himself, and the farmer invites him to have zakuski, or snacks with vodka. "Alcohol, sausage, live pigs," Tesson writes. "I'm living a Muslim's nightmare." Soon drunk, the author counts only forty-nine pigs in the barn. He and his host place bets and slip in the mud and filth as they loudly try to count the frightened animals. The next day, Tesson wakes up late in an empty building, apocalyptically hung over, and continues toward Lake Baikal.

Tesson suggests: "If you publish something where credibility is an issue, don't ever say you've seen a yeti."

He spends eleven days walking along the edge of the world's largest freshwater lake by volume.

Bears still concern him. He meets more isolated, drunk locals in villages near the lake; one encourages him to toast the regional anti-alcoholism campaign. As a guest at a monastery, he witnesses "something I have already noted with many monks: how spirtually developed people take pleasure in crudely serving soup."

When, halfway through the book, Tesson finally arrives at the Mongolian border, the reader can't help but think, even if it was already known, that Siberia is incomprehensibly enormous.

Mongolia

A local accompanies Tesson to Sükhbaatar, a small town where he can buy a horse.

Visitors from Salt Lake City got there before him. They've converted the local Buddhists into Mormons who drink hot water instead of tea, and whose only reservation with Christian doctrine is: "If Jesus is the celestial knight, why would he ride into Jerusalem on a donkey?"

That's not a wolf's paw in the top left corner, but it does belong to the descendant of a wolf. |

After two weeks of research on Rawicz in Ulaanbaatar, the capital, Tesson advances across the Mongolian steppe. He passes villages and the occasional sprinkling of yurts, then plunges into the heart of the northeastern section of the Gobi Desert on horseback.

The key to a successful crossing, he says, is to visit every well on the map. The journey takes ten days. He stays hydrated, but the entries in his diary are ominous.

Day 4: Another day offered to nothingness. (...)

Day 7: A dead camel. A cricket. Some shrubs. That's everything I laid eyes on today.

In Shivee Khuren, at the Chinese border, the checkpoint is closed to foreigners. The exhausted Tesson must backtrack along a huge triangle to enter China legally and return to Shivee Khuren. What could have been a 2500 meter (1.5 mi) crossing ends up being a 2500 kilometer (1553 mi) detour.

Gina Says:

- So. Much. Vodka.

- A lot of advice about surviving bears.

- Dude, just stay in the hospital like the doctors told you to. Honestly.

China

The Chinese Gobi: "Every morning greets a triptych of [dust], emptiness, and wind. And night is a renewed tête-à-tête with the groups of stars whose beauty forbids you from closing your eyes."

Tesson crosses into Gansu, a province between the Gobi and the Tibetan Plateau. He uses this time to reflect on Rawicz—in particular, his mistakes. The Pole got so much about the Gobi and Gansu wrong.

And then his knee starts to hurt. Within a couple of days, the pain is crushing.

He limps his bicycle to Dunhuang, "an oasis on the Silk Road." With the help of a new American acquaintance, Tesson visits a hospital. The Chinese to English to French translation of his injury: "a rupture of the knitting of soft masses." Recommendation: one month of rest.

Tesson leaves after a week.

With the Gobi behind him, he limps slowly, like an ant crawling across a pavilion of pink marble, he says, through the Qaidam Basin: all rock, no plants. "Vegetation is geology's makeup," he observes. The landscape is "a naked beauty," its nothingness "the great Purity."

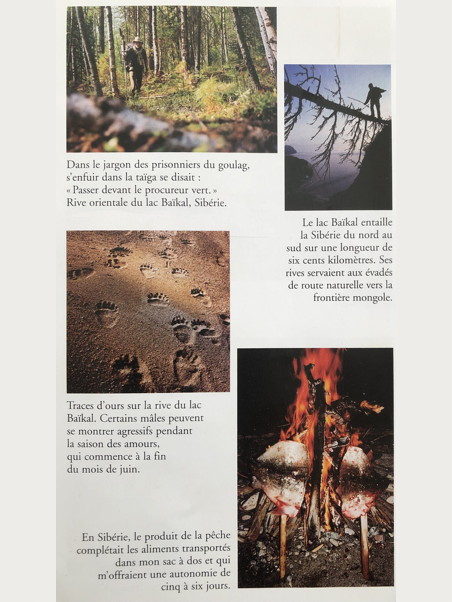

Top left: In Siberia, along Lake Baikal. Middle left: Bear tracks. |

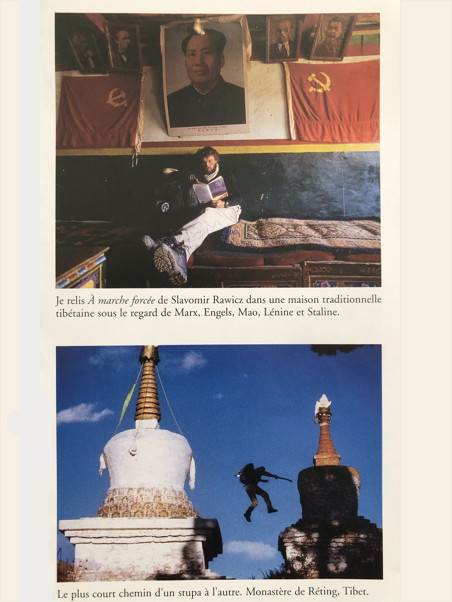

Top: Reading in a Tibetan home. Bottom: Moving between two stupas. |

With one leg much stronger than the other, he arrives in Golmud, ready to descend to Lhasa.

Tibet

Three Tibetan mastiffs celebrate Tesson's 150th day on the road by attacking him. In the village of Amdo, a family lets the author sleep in their home, then they lock him in his room. He accompanies monks on a pilgrimage and observes, "An escapee is Willpower walking, these pilgrims are Faith moving."

Surviving frigid temperatures and jagged mountains, and experiencing ample opprtunities to contemplate China's presence in Tibet, Tesson arrives in Lhasa. All that remains is "the final portcullis."

India

It had to be emotional, Tesson notes, for the fugitives on mountaintops to see lands two days away as the crow flies, but fifteen days away on foot due to the climbs and descents. So close, and yet.

He finally reaches Sikkim, a region of India, and begins a descent through snow toward the flat Indo-Gangetic Plain. The precipitation reminds him of Rawicz, as well as the decorated scientist Bernard Heuvelmans, who once made the tragic mistake of claiming to have met a yeti—an admission which, according to Tesson, saw Heuvelmans stripped of every title and academic position he ever held.

He spends eleven days walking along the edge of the world's largest freshwater lake by volume.

As for the subject, therefore, of "abominable snowmen" or, as Heuvelmans described them, "unknown homonids of the Himalayas," in case you were ever unsure of the proper course of action, Tesson suggests: "If you publish something where credibility is an issue, don't ever say you've seen a yeti."

During a stop in Darjeeling, Tesson visits a zoo specifically to see a red panda. In Calcutta, he takes a boat toward the city center. He ascends a stone stairway, hears the sounds of the streets, and for the first time on the trip, he wants to go home.

"I arrived at the end of the line," he writes. And with that, so does the reader.

The big but

From a certain perspective, I loved this book. It was beautifully written. Tesson has a sparkling vocabulary, especially for common words, and the escapist armchair travel was superb.

But.

Tesson said he wouldn't play detective with Rawicz, but so much of the book mentions the Pole. |

At the outset, Tesson rejects providing a definitive answer on whether Rawicz actually underwent the arduous journey of The Long Walk. In the final pages, he offers a platitude that Asia and its immensity "escape modern rationality," and, therefore, "it makes me happy to think Rawicz didn't lie."

So after 265 pages, during which he talks a great deal about Rawicz, it's fair to ask the question: if the book isn't about The Long Walk, what was the point?

Was it to learn that the author doesn't like Americans offering their help? That an erroneous map can get you killed? That he thinks alcohol and the internet are effective counterweights to revolution? (On the former, he's right; on the latter, he's absolutely wrong.)

The Wolf Axis is an epic struggle, with the ordeals' sharp edges sanded down so as not to upstage the author crossing the finish line. Okay. But the man counting pigs in Russia is the same as the one looking at sad red pandas in India. He hasn't changed. Which means you'll either like the Asian travel porn and trenchant observations, or you'll wonder why you picked up this book.

Click here to list the 44 Reviews which have already been published.

Volcanoes, Palm Trees, and Privilege

The Art of Travel

Blog Home

Recent Posts

Eyewitness Travel: France 4/24/2023

L'Africain du Groenland 8/2/2022

On the Plain of Snakes 5/17/2022

Volcanoes, Palm Trees, and Privilege 3/22/2022

L'axe du loup 2/28/2022

The Art of Travel 12/31/2021

Postcard: Los Angeles 11/5/2021

Afropean 8/6/2021

Roadrunner 7/22/2021

Popular Tags

Archive

Show moreAbout

Recent Tweets

If you toggle the switch above the words "Recent Tweets" and it still says, "Nothing to see here - yet," it means the idiot who broke Twitter either hasn't gotten around to fixing this feature, or intentionally broke it to get us to pay for it (which is moronic, I can easily live without it and it generated traffic to his site).

Add a comment

Comments