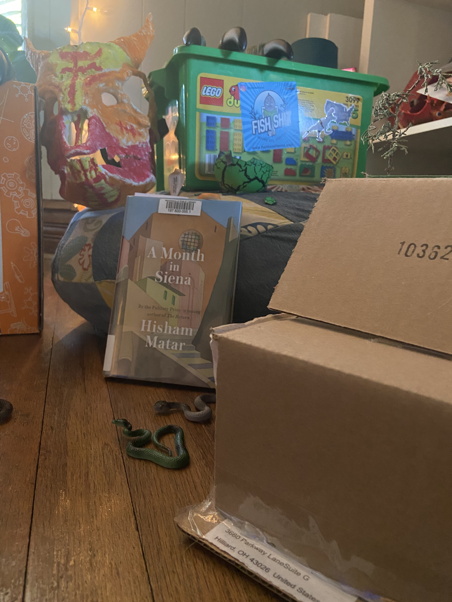

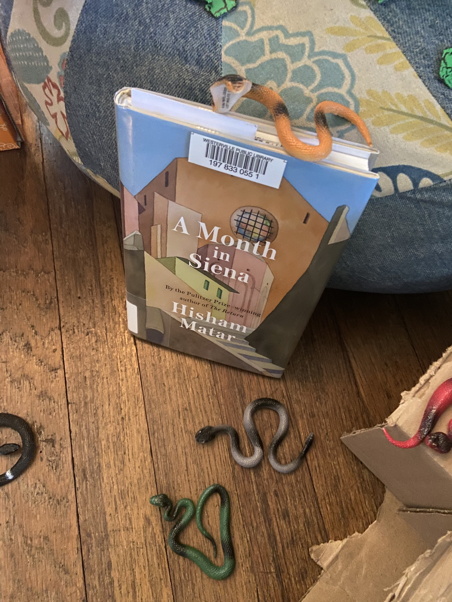

A Month in Siena 10/16/2023

A Month in Siena

by Hisham Matar

Review: A Month in Siena(2019), by Hisham Matar. Arrangement by Francis Tann. October 2023.

Reading time: 4 minutes

Return to Blog Home

October 16th, 2023 at 11:54am

Please consider disabling your ad blocker, it disrupts site functions in addition to blocking ads. Thank you!

I wanted something to happen.

In the follow-up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir The Return (2016), Hisham Matar goes to northern Italy with the intention of contemplating art.

Background on this series is here.

And...that's exactly what he does. He looks at paintings and writes about them.

We meet one or two of Matar's friends, he walks around the medieval town fifty miles south of Florence, and he tells some stories, but little else happens.

That's right. Matar's going to synthesize the brutality of political assassination with art history and navel gazing.

And so, despite lovely prose, themes of mourning and recognition developed in wisps, hints, and allusions, and the occasional masterful observation, A Month in Siena's most appealing quality is its compactness.

I don't say that out of snark. If someone recommended a book about a foreigner visiting Siena, but told you the author devoted little or no ink to food, activities, locals, or wacky language misunderstandings, and instead ruminated on death and absence in between comprehensive analyses of 600 year-old paintings—would you prefer to read, say, 300 pages of that, or 125?

Exactly.

Fortunately, that's what we have (127 pages, to be precise).

Paradise,Giovanni di Paolo, 1445 (Mods) |

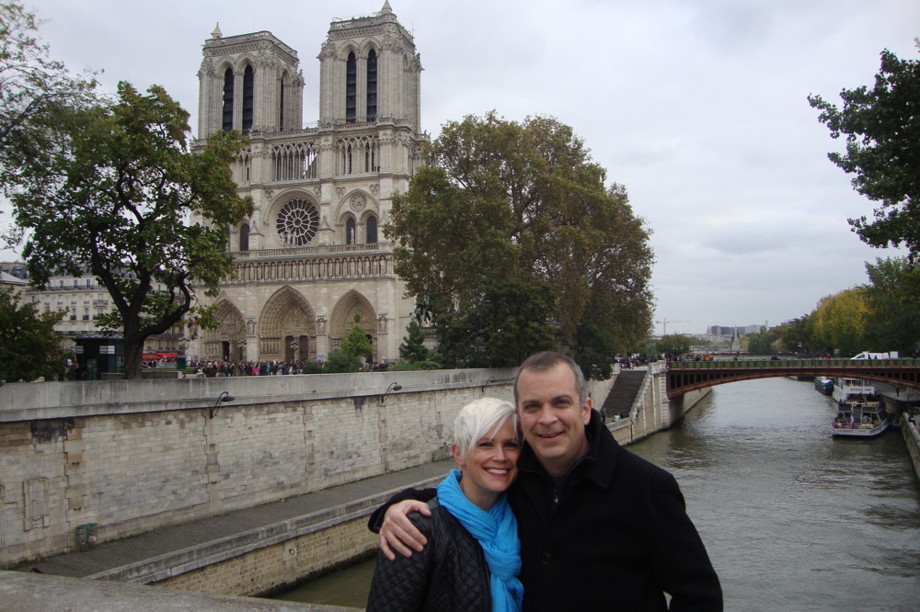

I took a 90-ish minute bus ride from Florence to Siena in 1996 |

Familiar Debut

A Month in Siena opens like a conventional travel memoir.

After more than three decades of being away I went back to Libya, the place where I grew up...Three years later I completed [a] book...It was then that I decided to go to Siena. I have for a long time been interested in Sienese art. But, now that I was finally going, my mind began devising ways of delaying my arrival. It was as though the long years of anticipation had created a reticence.

After presenting a psychological conflict, Matar discusses his itinerary and means of completing it (fly to Florence, walk to Siena), as well as the circumstances that prevent either from happening (mechanical issues, a twisted knee).

The setup feels familiar. And then, a mere six pages in, we learn a lot in just a few sentences.

The Real Gig

In 1990, Matar's father, an exile living in Cairo, was kidnapped and taken back to Libya where, "like salt dissolving in water, [he] was made to vanish."

Faced with the horrifying reality of a disappeared father—an emotional simpleton would bemoan the lack of "closure"—the author, studying in London at the time, acquires the habit of staring at Sienese art on his lunch break. He claims the reasons why "still remain unclear," but it seems obvious the pastime is a mechanism for coping with trauma. Sienese art belongs to "a cloistered world of Christian codes and symbolism," providing Matar with a distraction to unlock.

Over thirty years later, after writing The Return, his old habit calls to him again. This time he's headed to the source.

Allegory of Good Government,Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 1339; photo by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro CC BY-SA 4.0 (Mods) |

Since Matar is a literature professor at Barnard, the book will be an intellectual affair. He will not take a lover, discover a new dish (I had no idea I could enjoy artichokes this much!), or involuntarily shed a tear as he watches the sun rise over the Adriatic.

No, he's going to gaze at 14th and 15th century paintings and reflect. He'll explain how an object is analgous to an unrelated entity. He's going to tell you how something reminded him of something else, then tell you about that. He might throw in a dream or two.

That's right: Matar's going to synthesize the brutality of political assassination with art history and navel gazing.

It's not that bad

Truth be told, it's not as bad as it sounds.

An emotional simpleton would bemoan the lack of "closure."

Despite the clunky opening page above and my bad edits, Matar's sentences are clean and artful. Even if the content can be ponderous, the form moves along nicely.

The writerly sentences range from unexpected metaphors:

The sharp turns of [Siena's] passageways and the closeness of the buildings gave me the sense that I was entering a living organism.

...to bold declarations which are either silly or brilliant (or both) under the surface:

Any kind of faith, regardless of how adamant it might appear, is a space of doubt.

...to observations containing trite but undeniable truths:

I remember thinking...that dying now would be a waste, given how much time I had spent learning to live.

...to intellectual meanderings:

I could see from Siena's point of view that infinity is a claustrophobic prospect, that it is perfectly appropriate, given the chaotic nature of life, to cordon off an area in which to interpret ourselves, where one can decide what is important, what is to be privileged and what to be left out, determine the axes of the main thoroughfares and the arrangement of the streets between them.

The brain of the matter

Matar meets a Jordanian family in Siena, and reunites with Beatrice, an old friend—"old in time and in age"—who tells him about a baby she lost pre-term. The death creates a balance I found tragic as a human being, but satisfying as a structuralist: man loses parent, woman loses child.

He also gives an interesting history lesson on the Black Death, and offers a thesis I have considered before: that rooms contain qualities of the activities that took place in them. This is why some spaces, even when empty, feel joyful, tragic, stressful, etc.

But a majority of A Month in Siena is devoted to analysis of masterworks of art.

"I thought if either of us moved the subject too would change." |

Madonna del latte,Lorenzetti, 1325; photo by Sailko CC BY 3.0 (Mods) |

What I enjoy about Matar's reading of these Sienese classics is that, like a good scholar, he's not afraid to expand an observation; the reader may be tempted to disagree reactively, but upon closer inpsection, one sees he's usually right.

In Lorenzetti's Madonna del latte (1325), for example, the author says of the Christ child's suckling, "there is a sexual quality to his excitement. (...) This is a child who has no qualms about his appetites." After looking twice, I saw it. (My wife did not.)

A Month in Siena feels like an excellent book to have written, but not an excellent book to have read.

Matar brings this bold eye to several paintings, but two appear to take precedence.

The first is the collection he spends the most time on: Lorenzetti's series on government in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico. He has many things to say about these paintings, particularly Allegory of Good Government. I couldn't see the images well and flipped past the many pages of interpretations, but of course, yes: go good government.

The second is his treatment at the end of the book of a lovely work by Giovanni di Paolo called Paradise (1445). In the painting (which he actually observes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), pairs of people hold hands and smile as they look into each other's eyes. Matar wonders if a specific couple are the epistolary lovers Héloïse and Abelard. In her letters, he says Héloïse "is wonderfully greedy when she asks [Abelard], Let me have a faithful account of all that concerns you."

Matar continues:

That must surely be the ambition of every reunion, not only to identify and be identified, but also to have an accurate account of all that has come since the last encounter.

Impossible resolution

Rare is the intellectual exercise that drops an emotionally satisfying mic. But A Month in Siena cannot, and Matar knows that.

The book opens with a Swiss Air flight from Zurich to Florence that turns around, but there's no ordeal. They end up taking a bus to Siena. |

His father is gone, probably. All the author knows is that he hasn't seen him for decades, and doesn't know where he is, whether dead or alive.

If Libya had a better government, if its elders had appealed to the Virtues watching over them, then the Vices would not have disappeared Matar's father. The world (Yes, the world, Lockerbie says) would be living closer to Lorenzetti's Effects of Good Government than the Effects of Bad Government.

Alas, Libya suffered under Gaddafi and is suffering now, in a fractured post-Arab Spring landscape. Matar can only hope that di Paolo is right, that the author will meet his father in paradise, where he can finally have a faithful account of all that concerns him.

Gina Says:

- It was short

- It's in Italy

- The dude suckin' on a titty: I didn't agree (she actually said that)

Conclusion

Ultimately, I found A Month in Siena to be unsatisfying. Its heavy intellectual approach clashed with the tragic content, and the occasionally precious analogies tarnished the genuinely fine writing elsewhere.

A Month in Siena feels like an excellent book to have written, but not an excellent book to have read. I'm unsure if it would even have been published if Matar had not recently won a Pulitzer Prize.

Click here to list the 44 Reviews which have already been published.

Recent Posts

Eyewitness Travel: France 4/24/2023

L'Africain du Groenland 8/2/2022

On the Plain of Snakes 5/17/2022

Volcanoes, Palm Trees, and Privilege 3/22/2022

L'axe du loup 2/28/2022

The Art of Travel 12/31/2021

Postcard: Los Angeles 11/5/2021

Afropean 8/6/2021

Roadrunner 7/22/2021

Popular Tags

Archive

Show moreAbout

Recent Tweets

If you toggle the switch above the words "Recent Tweets" and it still says, "Nothing to see here - yet," it means the idiot who broke Twitter either hasn't gotten around to fixing this feature, or intentionally broke it to get us to pay for it (which is moronic, I can easily live without it and it generated traffic to his site).

Add a comment

Comments